Who built the fastest humanoid sprinter? How well can a robot recover from a fall? And can machines really box or play soccer with human-like intelligence?

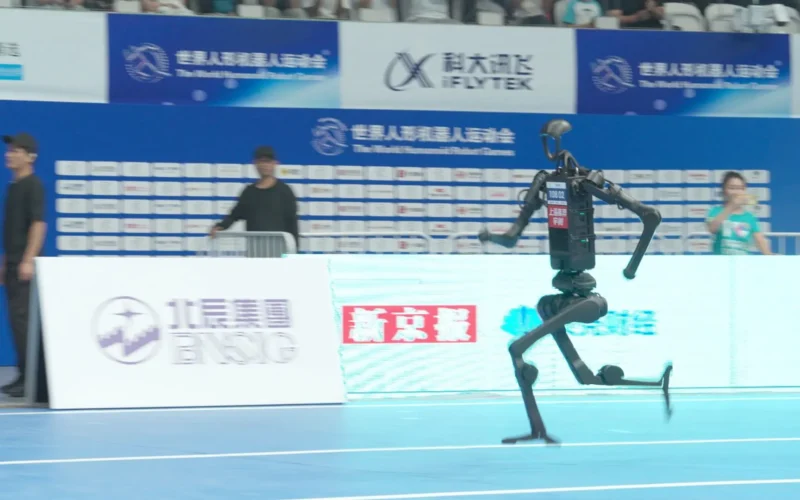

Those questions drove the world’s first World Humanoid Robot Games, which concluded Sunday in Beijing, marking what experts called a milestone in both competitive robotics and next-generation machine autonomy.

The three-day event, hosted at the National Speed Skating Oval from August 15 to 17, drew 280 teams from 16 countries, fielding more than 500 humanoid robots across 26 disciplines, including sprinting, boxing, table tennis, gymnastics, soccer, and material-handling trials.

For China, the event carried broader significance: it positioned Beijing not only as the inaugural host but also as a leading hub in humanoid robotics research, production, and large-scale deployment.

Organizers confirmed that the second edition of the Games will also be held in the city in 2026, consolidating what some are already calling the “Robot Olympics.”

China’s domination and technical showcases

China’s robotics champions, Unitree Robotics and X-Humanoid, emerged as the Games’ top winners.

Hangzhou-based Unitree collected 11 medals, including four golds, dominating track-and-field events such as the 400-meter dash, 1,500-meter race, hurdles, and 4×100-meter relay.

Beijing’s X-Humanoid secured 10 medals, including two golds, excelling in the 100-meter sprint and factory-inspired material-handling challenges.

Unitree’s flagship H1 humanoid, priced at 650,000 yuan (about $90,000), drew attention for its advanced M107 joint motor, which delivers up to 360 newton-meters of torque.

That mechanical advantage allows for longer strides, faster sprints, and robust balance recovery – all vital benchmarks in humanoid locomotion.

By contrast, X-Humanoid’s Tien Kung platform, designed as an all-around performer, demonstrated steady autonomous running.

Unlike most competitors, which relied partly on remote operation, Tien Kung could run without human intervention, a key indicator of progress in onboard autonomy.

Other Chinese firms, including Neotix Robotics and Booster Robotics, claimed medals in gymnastics, long jump, and football.

International participants, while competitive, largely used Chinese-built humanoid platforms, applying their own AI algorithms on top – a sign, organizers said, of the country’s growing hardware dominance.

Technical milestones: Motion control, sensors, and AI

Experts highlighted that the Games were less about medal counts and more about testing the frontier of humanoid robotics.

Zhou Changjiu, president of the RoboCup Asia-Pacific Confederation and one of the co-organizers, said the event represented a “test field” for balance, motion control, and decision-making in humanoid machines.

“Soccer robots operated fully autonomously, relying on AI for strategy, while boxing was remotely piloted, testing teleoperation frameworks,” Zhou explained.

“Both reveal distinct decision-making architectures that can be generalized to industrial, domestic, or rescue operations.”

Humanoid robots are fascinating creations that integrate various technologies to mimic human-like behavior.

At their core, they consist of three key layers. The first layer is the “body,” which refers to the mechanical hardware of the robot.

It includes components such as actuators, torque motors, and structural materials that provide the physical form and functionality required for movement.

The second layer is known as the “cerebellum.” This part contains the motion-control systems that are responsible for managing the robot’s gait, posture, and fine-motor coordination.

It allows the robot to move fluidly and adapt its movements to different situations, much like an actual human would.

Finally, the top layer is the “brain,” which involves artificial intelligence (AI) cognition. The layer enables the robot to process perception, planning, and decision-making, allowing it to interact intelligently with its environment.

Together, these three layers create a sophisticated system that allows humanoid robots to operate in a variety of settings and perform tasks that require a level of human-like understanding and response.

From competition to real-world applications

While hardware and motion control have reached advanced levels, Zhou noted that AI cognition – particularly environmental understanding and situational awareness – remains the limiting factor.

“Robots do not yet perceive the physical world with human-like comprehension,” he said. “That is the gap that must be closed for integration into homes, factories, and hospitals.”

Recent advances in sensor fusion, combining LiDAR, stereo vision, inertial measurement units, and force-torque sensors, have dramatically improved a robot’s ability to map its surroundings, detect obstacles, and maintain stability.

Yet AI-driven contextual decision-making still lags behind.

Organizers said the Games’ events were designed with real-world parallels. Sprint races tested battery endurance, actuator efficiency, and balance recovery under high acceleration.

Boxing measured the responsiveness of upper-limb control under dynamic, adversarial conditions. Material-handling trials simulated industrial workflows, evaluating robots’ ability to carry and manipulate objects in cluttered environments.

These benchmarks, said Tang Jian, CTO of X-Humanoid, serve as “proxy tests” for broader deployment.

“A humanoid that can sprint, balance after impact, or manipulate irregular objects is one step closer to functioning in factories, logistics hubs, or even disaster zones,” he said.

The implications go beyond spectacle. IDC projects the global robotics market will hit $400 billion by 2029, with humanoid robots forming a key growth sector.

China alone could account for half of that value, fueled by state subsidies exceeding $20 billion and rising integration of humanoids into state-owned enterprises.

Toward a “Robot Olympics”

The event culminated with the launch of the World Humanoid Robotics Games Federation, established by the World Robot Cooperation Organization, the Global Digital Economy Cities Alliance, the RoboCup Asia-Pacific Confederation, and the Chinese Institute of Electronics.

The Federation aims to standardize rules, expand global participation, and formalize the Games into a recurring event.

For robotics veterans like Zhou, who has worked in humanoid robotics for nearly 30 years, the Games mark the beginning of a new chapter.

“This is the birth of the humanoid robot Olympics,” he said. “Just as Ancient Greece gave rise to the Olympics, future generations may see Beijing as the birthplace of the humanoid robot era.”

Despite impressive performances, the Games also exposed limitations. Robots frequently tripped, froze mid-action, or toppled during kickboxing matches.

“It’s an exploratory process for both humans and robots,” said Zhang Jidong, a Tsinghua University professor who served as an international referee.

“Rules, judging systems, and event design are all evolving alongside the machines themselves.”

Advancing humanoid robots

Researchers have identified three key areas that require breakthroughs to advance technology significantly.

The first area is energy density. Current lithium-ion batteries often limit operational time, particularly for applications that demand high-power locomotion.

Exploring alternatives like solid-state batteries or hydrogen fuel cells could potentially extend endurance and enhance performance.

The second area of focus is AI cognition. A persistent challenge exists in bridging the gap between perception and contextual reasoning.

Promising techniques such as embodied AI and reinforcement learning within physics simulators are being investigated to address this.

These approaches may lead to significant advancements in how machines understand and interact with their environments.

Lastly, material science plays a crucial role in advancing robotics. The development of lightweight composites and soft robotics holds the potential to improve resilience in robotic systems.

Such innovations would enable robots to absorb impacts and recover more naturally, enhancing their effectiveness in various tasks and environments.

Together, breakthroughs in these areas could drive remarkable progress in technology and robotics.

The road ahead

Over the next decade, humanoids are expected to evolve from research prototypes into multipurpose platforms across logistics, elder care, education, and defense.

By 2030, experts predict humanoid robots will move from controlled test environments to semi-structured real-world deployment at scale.

For enthusiasts and engineers alike, Beijing’s inaugural Games offered entertainment and a glimpse into the state of the art.

The sight of a Unitree H1 sprinting under AI control or a Tien Kung autonomously completing a race marked incremental but tangible progress toward human-machine parity in locomotion and interaction.

Whether the event will truly become the “Robot Olympics” remains to be seen.

But in technical circles, the consensus was clear: the first World Humanoid Robot Games demonstrated both how far humanoids have come and how far they still have to go.

Banner image: A Unitree robot participating in the world’s first humanoid robot Olympics held in China. (Credit: Unitree)