The Moon, once a silent backdrop for poets and dreamers, is becoming the focal point of a new global competition. In 2025, the United States, China, and Russia are advancing plans to deploy nuclear power plants on the lunar surface – a step that could enable permanent settlements, mining operations, and a new era of interplanetary exploration.

What once sounded like science fiction is rapidly moving toward reality. With its thin atmosphere, extreme temperature swings, and nights that last 14 Earth days, the lunar environment poses challenges that traditional solar panels cannot reliably overcome. With its ability to deliver steady and compact power, nuclear technology is emerging as the only practical solution to sustain human outposts.

Why Nuclear Power on the Moon?

For decades, space missions relied on solar arrays and chemical batteries. But while solar power is abundant during lunar daytime, the two-week darkness renders panels almost useless. Batteries, meanwhile, are limited in capacity and unsuitable for long-term human bases.

Nuclear reactors provide a way around this. Compact fission systems – splitting uranium or other heavy elements – can generate continuous energy regardless of sunlight. Advanced designs are being tested to withstand harsh radiation, lunar dust, and the Moon’s one-sixth gravity.

Fusion, which powers the Sun, is also on the horizon. Though not yet commercially viable on Earth, some analysts believe the Moon’s surface could supply helium-3, a rare isotope often described as a “clean fusion fuel.” Large deposits of helium-3 embedded in lunar soil have drawn the interest of space agencies and corporations, positioning the Moon as a potential future energy hub.

From Cold War Prestige to Energy Security

The first race to the Moon in the 1960s was about prestige and ideological dominance between the United States and the Soviet Union. The new race is about energy, sustainability, and the control of resources that could shape the future of civilization.

The US is advancing its nuclear ambitions under NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface and establish a long-term base at the Moon’s south pole. Lockheed Martin, Westinghouse, and other contractors are working on compact fission surface power systems capable of generating up to 10 kilowatts of electricity – enough to run habitats, laboratories, and life-support systems.

China has mapped out a similar strategy. Its Chang’e lunar missions have already demonstrated precision landings, rover operations, and sample return capabilities. Beijing has openly stated its intent to build a lunar research base by the 2030s, with nuclear energy likely playing a central role.

Russia, despite economic pressures, continues to see the Moon as a strategic prize. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has floated concepts for nuclear-powered infrastructure, linking such projects to the country’s long history of nuclear engineering in space. The Soviet Union launched dozens of nuclear-powered satellites during the Cold War, and Russia is adapting that legacy for future missions.

Technology at the Core

Developing a nuclear reactor for the Moon requires rethinking conventional engineering. Reactors must be light enough to launch aboard rockets, shielded against radiation hazards, and capable of running unattended for years.

US engineers are experimenting with kilopower reactors – small systems that use uranium fuel rods, liquid metal cooling, and Stirling engines to convert heat into electricity. These designs can be assembled on Earth, transported in modules, and activated after landing on the Moon.

China has hinted at similar projects while focusing on helium-3 extraction technologies. If fusion power becomes practical, helium-3 could transform the global energy market. Advocates claim that a single ton of helium-3 could produce as much energy as 15 million barrels of oil, without the radioactive waste associated with fission.

Russia, meanwhile, has tested nuclear propulsion systems for deep-space missions. These designs could double as lunar power plants, providing electricity for bases and mining outposts.

The Legal Grey Zone

While technology advances, the legal framework governing lunar nuclear plants remains murky. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, signed by more than 100 nations, forbids countries from claiming sovereignty over celestial bodies. It also bans the placement of nuclear weapons in orbit or on the Moon. However, the treaty does not explicitly prohibit nuclear power plants.

That leaves a loophole: nations can build reactors so long as they are for peaceful use. However, once a facility is established, it raises questions about control. If a US reactor is built near helium-3 deposits, would that constitute a de facto territorial claim? Could “safety zones” around such facilities evolve into exclusive zones of operation?

The United States has already introduced the Artemis Accords, non-binding agreements with allied nations that outline best practices for space exploration. These include provisions for safety zones to prevent interference. Critics argue that while these zones are intended for safety, they could serve as legal cover for long-term control over lunar territory.

China and Russia, not part of the accords, accuse Washington of trying to rewrite space law in its favor. They argue that the Moon should remain a “province of all humankind,” open equally to all nations.

Risks of Nuclear Power in Space

Nuclear energy in space is not without precedent. The United States has launched radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) to power spacecraft like Voyager, Cassini, and Perseverance. The Soviet Union, however, left a cautionary tale: in 1978, its Kosmos 954 satellite crashed in Canada, scattering radioactive debris across vast areas. The Soviet government eventually paid millions in damages.

On the Moon, the risks are different but no less serious. A malfunctioning reactor could contaminate lunar soil, disrupting future operations and sparking diplomatic disputes. Cleanup would be technically challenging and politically costly. The lack of a clear international enforcement mechanism adds to the danger.

Unlike the Cold War, today’s space race includes private actors. SpaceX, Blue Origin, and other companies are positioning themselves as contractors for lunar infrastructure. International law holds their home governments responsible for oversight if private firms build reactors. This means any accident or dispute could quickly escalate into a state-level issue.

The dual-use nature of nuclear technology complicates matters further. A reactor that powers habitats could also support military assets, such as surveillance systems or communication relays. This blurring of civilian and strategic purposes risks sparking mistrust among nations.

The Geopolitics of Helium-3

At the heart of the nuclear race lies helium-3. The isotope, carried to the lunar surface by billions of years of solar winds, is almost absent on Earth. Advocates see it as the ultimate fusion fuel, capable of producing massive energy without greenhouse gas emissions.

Mining helium-3, however, would require industrial-scale operations – lunar excavation machines, processing plants, and, crucially, nuclear power to keep them running. Whoever controls helium-3 could potentially control the future of fusion energy, making it both a scientific and geopolitical prize.

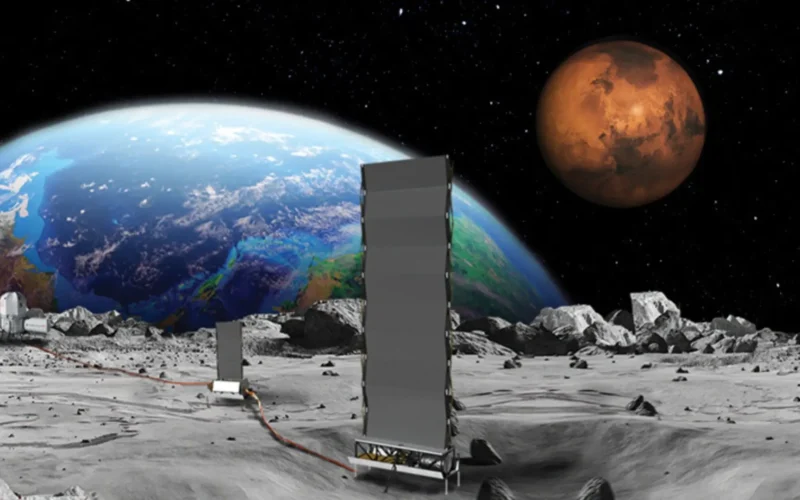

The deployment of nuclear reactors on the Moon will likely begin modestly, with kilowatt-scale systems powering small bases. Over time, as technology matures, larger reactors could support entire settlements, mining colonies, and even fuel depots for missions to Mars.

But with opportunity comes risk. Each new nuclear installation increases the chance of disputes over territory, safety, and resource rights. Without stronger international agreements, the Moon could shift from a symbol of global unity to a flashpoint of competition.

The coming decade will be decisive. If the US, China, and Russia succeed in building nuclear power plants on the lunar surface, they will not just be powering habitats – they will be defining the rules of a new era in space. Whether this future will be cooperative, benefiting all humankind, or competitive, driven by national ambition and resource control.

The Moon is no longer just a beacon in the night sky. It is the proving ground for humanity’s most ambitious technologies – and its deepest geopolitical rivalries.